The Wagner tuba’s inclusion in the orchestra had its supporters in Heinrich Rietsch, Alfred Orel and Fritz Oeser but, even so, most composers didn’t trust themselves to write for it. Humperdinck warned against its casual deployment and Mahler gave thought to using them but ultimately excluded them. Only a handful of post-Wagnerians actually composed for them:

The Wagner tuba’s inclusion in the orchestra had its supporters in Heinrich Rietsch, Alfred Orel and Fritz Oeser but, even so, most composers didn’t trust themselves to write for it. Humperdinck warned against its casual deployment and Mahler gave thought to using them but ultimately excluded them. Only a handful of post-Wagnerians actually composed for them:

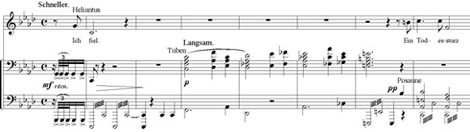

Adalbert von Goldschmidt (1848-1906) (Photo left) in ‘Heliantus’ (1884); Jean Louis Nicode (1853-1919) in ‘Das Meer’ Op. 31 (1891); Friedrich Klose (1862-1942) – who had lessons with Bruckner – in ‘Der Sonne-Geist’ (1917); and Felix Draeseke (1835-1913) in ‘Jubel-Ouverture’ Op. 65 (1898) in which Draeseke uses two B-flat tenor tubas & two basses in F, which are employed separately and in a jolly, galloping manner (a far cry from the hieratical tones of Wagner and Bruckner, a divergence for which he was rebuked by Richard Strauss). Below: Goldschmidt’s Heliantus

Richard Strauss also used the instruments in ‘Guntram’ Op. 25 (1893), ‘Don Quixote’ Op. 35 (1898), ‘Ein Heldenleben’ Op. 40 (1899) and ‘Elektra’ (1909). Strauss’s most intensive continuous occupation with the Wagner tuba was during the years 1913-17 in ‘Josephs Legende’ Op 63 (1914), ‘Eine Alpensinfonie’ Op 64 (1915) and ‘Die Frau ohne Schatten’ Op 65 (premiered in1919).

In ‘Don Quixote’ he was the first to use a mute for the Wagner tuba, and both this work and ‘Ein Heldenleben’ are scored for a single tenor tuba in B-flat. ‘Elektra’ contains what may be the most difficult tuba parts in existence in an about-face from his critique of Draeseke’s “dancing tubas”. They assume a very important place in the opera’s sound world. After 1919 he never again composed for the Wagner tuba. Indeed, Strauss later came to think that his solo Wagner tuba parts were generally better off played on euphoniums, baritones or tenor horns – “better than the rough and inflexible tuba with its demonic noise,” was his comment.

Wagner tuba parts were typically played by existing military instruments outside the German-speaking world. Substitution (variously by cornophones, Saxhorns, tubettes, tenor horns or euphoniums, or tuba instruments built along Sax lines) was also the norm in Great Britain, but the first true English Wagner tuba quartet (from Alexander in Mainz) made its debut in the Covent Garden Ring cycles in Spring 1935. The United States, because it imported many German hornists, had authentic Wagner tubas from quite early on.

With the major opera houses in Germany and Austria all having sets of Wagner tubas by the early twentieth century, there was consequently a finite market for the instruments. Makers like Enders (Mainz), Schopf (Munich) Schopper (Leipzig), Reissmann (Chemnitz) and the Produktiv-Genossenschaft der Instrumentmacher (Vienna) found the market a crowded one, vying with Gbr. Alexander (Mainz), Eschenbach (Dresden), Knopf (Markneukirchen), Ed. Kruspe (Erfurt), C.W. Moritz (Berlin), Piering (Adorf), C.F. Schmidt (Berlin-Weimar) and Uhlmann (Vienna). They were saved by the military bands in Prussia and imperial Germany which took on use of the instruments more and more to replace horns in march music and so be loud enough to compete in the open air.

Next Essay – Modern Voices